He was a small man. To crease the air past five foot five, he needed to sculpt his hair upwards — when he had it, before the wigs — and wear lifts in his boots. But the sound he made was huge, massed ensembles of drums, bass, and guitar (in that order), reinforced by percussion, boosted by brass, and sweetened with perfectly placed instrumental hooks — indelible guitar or horn fills, backing vocals, or more drums, the bigger the better. He was obsessed with music — its sound and its business. He liked to fight — Marshall Leib, a high-school friend and part of his first band, The Teddy Bears, remembered having to step in to save him from the trouble his mouth would provoke. Yet he made his great subject love, and in particular the overwhelming, and impossible to sustain, power of love’s first flush: “(Today I Met ) The Boy I’m Going to Marry,” “And Then He Kissed Me,” “He’s Sure the Boy I Love,” “Be My Baby,” “Baby I Love You,” “To Know Him is to Love Him.”

It would be too simple to say that Phil Spector’s art created the world he couldn’t create for himself — a tortured, toxic and finally murderous man crafting hit after hit about idealized romance — but there is no getting around it. It is everywhere in his early music, never more clearly than in one of the first hits he made when he started his own label, Philles, “Uptown,” by The Crystals, written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil and a Billboard Hot 100 No. 13 in 1962. “He’s lost in an angry land. He’s a little man. But then he comes uptown each evening to my tenement . . . And when he’s there with me he can see that he’s everything. Then he’s tall, he don’t crawl. He’s a king.”

In creating his kingdom, Spector — who died at the age of 81 on Jan. 17 — cemented the idea of the producer as auteur and the recording studio as a canvas. Both would doubtless have come into being without him and his Wall of Sound — the early days of rock’n’roll are filled with producers in search of new sounds and new techniques, most notably Sam Phillips recording Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis in the Sun Studios space he designed with vaulted ceilings like a church, and Bumps Blackwell laboring endlessly over mic placement to get just the right feel as he worked to capture the hurricane of sexuality known as Little Richard. And artists like Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison recognized the possibilities of the studio to bring new complexity to their sounds.

But Spector was different. At the start, on The Teddy Bears’ “To Know Him is To Love Him” — a rephrasing of the epitaph from his father’s gravestone that Spector turned into a Hot 100 No. 1 in 1958 — his sound was not so very far removed from the other recordings of the day, many of which carried the spacious aura of the rooms in which they were cut, investing early rock and pop with the mystical sense that new frontiers were being explored. Eventually though, he recognized how to make that aura the centerpiece of his records. You can hear how he did just that in the very first hit on Philles, The Crystals’ “There’s No Other Like My Baby” from 1962. Built like a rocket with three stages, it begins simply, with bass, guitar and voice rippling outward in stark echo before a piano part that seems borrowed from The Chantels’ 1958 classic “Maybe” lifts the song skyward with a burst of sound. Then chorus vocals, glockenspiel and strings continue the song’s journey toward the heavens. Three years later, The Beach Boys — whose Brian Wilson would find both personal intimacies and cosmic dimensions in Spector’s studio technique and session musicians — would cover the song, bringing out its connections to ’50s doo-wop on a live album recorded in the months before they began work on Pet Sounds.

Spector called his music “pop blues.” He mixed light and dark emotions in ways few could with any consistency, yet he could do it time and again, with spectacular clarity. In the early ’60s — the supposedly fallow time in which rock’n’roll was dead — the Philles label scored 17 top 40 hits, titanic expressions of youthful pain and triumph, delivered with a passion that bordered on rage. He was not alone — Motown’s hit factory was flowering at the same time — but he helped to set the stage for the explosion that The Beatles sparked when they reached the U.S. in February 1964.

Spector was different in other ways that helped make him and his music mythic. He was a fast-talking hipster, able to capture the interest of those outside the immediate reach of pop and rock and roll by invoking the totems of high culture. He said his records were built like little Wagner operas, conceived like art movies, a product of his mind. Among those who noticed was Tom Wolfe, who dubbed Spector “The First Tycoon of Teen” in a 1965 story of the same name for New York magazine, then a supplement for daily newspaper the New York Herald. (Tellingly, the piece begins with Spector displaying the neurosis that drove him, as he insists a plane on the runway turn around and let him off, because he’s sure it will crash.)

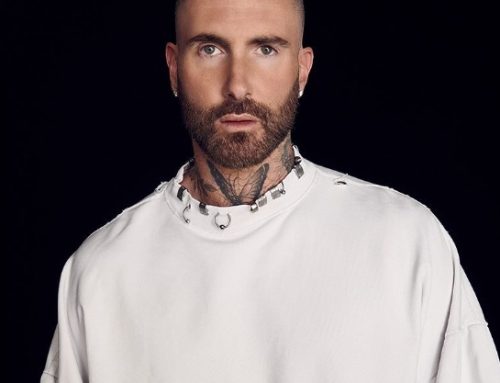

Bbc Arena/Vixpix/Kobal/Shutterstock

Phil Spector and John Lennon

The sobriquet stuck, as did the image of Spector as a singular genius, though the Wolfe piece arrived just as Spector’s run of hits began to dry up. He placed four songs by The Righteous Brothers on the charts in 1965 — with “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feeling” hitting No. 1 — then did not see the top 20 again until 1969, when his production of “Black Pearl” for The Checkmates brought Spector’s sleigh bells and strings into the soul era.

As a new decade dawned, Spector began his last run of greatness, doing much to shape the shaggy-haired, hippie-haute rock that ruled the ’70s. Having befriended The Rolling Stones in the mid-’60s, he found himself connecting to The Beatles through Stones-turned-Beatles manager Allen Klein. In January 1970, Spector went to London to produce “Instant Karma” for John Lennon. As Mark Ribowsky recounts in his Spector biography He’s A Rebel, in a display of ego Spector kept Lennon waiting for an hour at Abbey Road Studios, and the session had already begun by the time he arrived. But once there, he worked quickly. The song was done in 10 takes, with Spector layering several piano tracks and electric keyboard and overdubbing Alan White’s drums to create a tumbling sound that recalled the slapback echo of early rockabilly. It was a remarkable collision of spontaneity and deliberate craft, and it went to No. 3 on the Hot 100. Flush with the success of the Lennon single, Spector was tasked with salvaging the tapes that would become Let It Be, much to the displeasure of Paul McCartney (and many critics at the time), who disliked his orchestral and choral additions.

Just the same, Spector would cast a long shadow over the early ’70s. George Harrison, on hand to play guitar on “Instant Karma,” recognized the way Spector brought his Wall of Sound to a five-piece rock band and tapped him to produce his first solo album, All Things Must Pass, a triple LP that went straight to No. 1 on the Billboard 200. Then in June 1970, Spector produced the first single from the new band Harrison’s friend Eric Clapton had recently put together, Derek and the Dominos (though the Spector version of “Tell the Truth” would be quickly withdrawn when Clapton recut it a few months later). In August, Joe Cocker released Mad Dogs & Englishmen, a live double album co-produced by Cocker’s musical director, Leon Russell — who’d played piano on many Spector sessions in Los Angeles. The 11-piece band (plus a 10-person backing choir) assembled by Russell included two drummers and showed how Spector’s studio visions could be translated to the stage.

Thus established, Spector co-produced Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh benefit concert and album in 1971 — another triple LP, which featured Bob Dylan, Clapton, Harrison and Ringo Starr, and which went to No. 2 on the Billboard 200. And Lennon would work with Spector again on his first two solo albums, Plastic Ono Band and Imagine. The first was a magnificent display of raw, minimalist rock’n’roll, while the title track of the second showed how Spector’s beloved strings could be successfully deployed to subtly reinforce the deceptive simplicity of Lennon’s most challenging song.

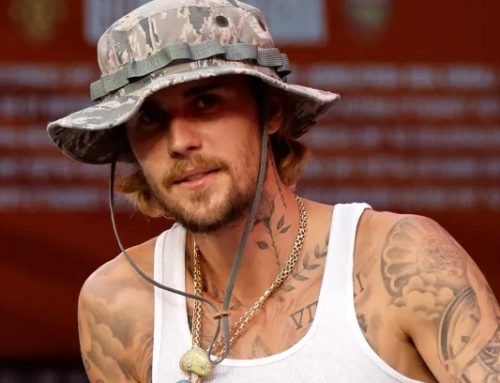

And then it was over, more or less. Spector’s work would continue to reverberate. Martin Scorcese scored the opening credits of his 1973 breakthrough film, Mean Streets, to The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” (and in 1990 used The Crystals’ “Then He Kissed Me” for the famed Copacabana tracking shot in Goodfellas). Bruce Springsteen drew on Spector’s Wall of Sound for his breakthrough, Born to Run. (“If you wanted to steal my sound, you shoulda gotten me to do it,” Spector cracked when Springsteen turned up at the Los Angeles sessions for a Dion DiMucci album Spector was producing.) The Ramones rewired Spector’s pop-blues machine to run on pop and punk on songs like “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend.” The Notorious B.I.G. changed the Crystals’ “Da Doo Ron Ron” to “your crew run run” on his hit “Hypnotize.” Amy Winehouse patterned part of her look after Spector’s second wife, Ronnie, and released a live performance of “To Know Him is to Love Him” as a B-side.

By the mid-’70s, though, Spector was lost inside his myth, rarely touching the world outside except to trouble it. The 1973 sessions for Lennon’s Rock‘n’Roll album included drunken rages and at least one gun shot into the studio ceiling. At 1975 sessions with Cher, Spector punched David Geffen, then Cher’s manager, dropping him to the floor. The 1979 sessions for The Ramones’ End of the Century generated stories of Spector holding the band hostage at gunpoint. Spector had begun the ’70s as a force and ended it as a caricature.

Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images for NARAS

Amy Winehouse performs at The Riverside Studios for the 50th Grammy Awards ceremony via video link on Feb. 10, 2008 in London.

His life was defined by toxic masculinity. His music was defined by simple statements of devotion. And this disjunction destroyed him. No matter how much money or respect the world gave him, it could never give him enough. It could never give him the power and control he found in his music.

On February 3, 2003, Spector met Lana Clarkson at a Los Angeles club on the Sunset Strip, took her to his hilltop home in Alhambra, Calif., and ended her life at 40. Compounding this tragedy is the fact that his malignancy had been in plain view for decades before that horrible night. There were plentiful stories of him brandishing guns, or his bodyguards making sure his violent behavior went unchecked, and his ex-wife, Ronnie, had spoken of being held captive in the Alhambra home. Barbed wire. Guard dogs. A gold coffin that Phil threatened to use to display her body if she dared to leave to him.

It would take five years and two trials to convict Spector after he shot and killed Clarkson. Two things stand out about his unrepentant conduct: When the police arrived, Spector told them “I didn’t mean to shoot her,” and despite this confession, failed to comply with their instructions to show his hands. He kept them in his pockets and refused to take them out. The small man acting big one more time. And so the LAPD tased him, resulting in two black eyes and a broken nose.

Months later, in an act of spectacular arrogance, Spector spoke with Scott Raab of Esquire, peddling the notion that the shooting was an “accidental suicide” that occurred when Clarkson “kissed the gun.” It was as though someone had held the mirror up to an ugly song Spector had recorded in 1962, “He Hit Me (And It Felt Like a Kiss),” and his rancid core had been revealed for all to see. All except for him.