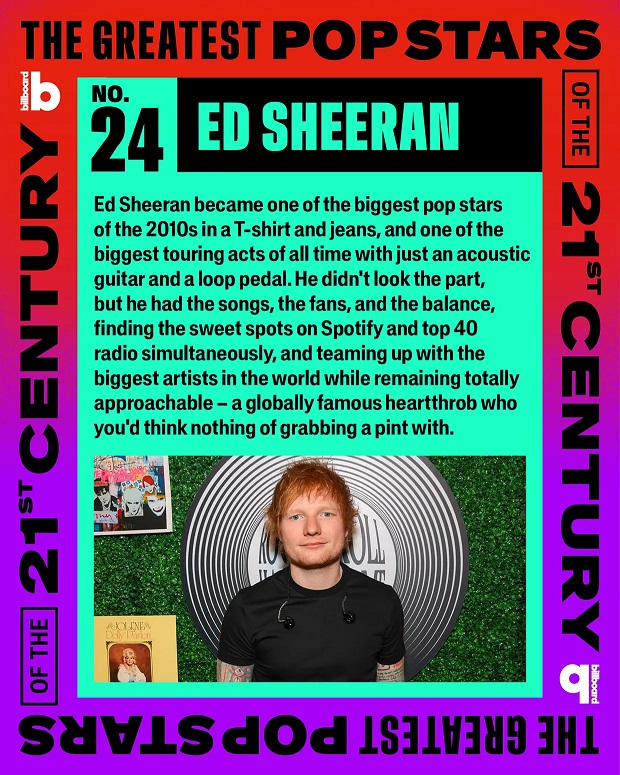

The megastar’s talents are often undercut because of his mass appeal. Here’s why that’s unfair.

Despite being one of this century’s most successful musicians by pretty much any statistic you could conjure, Ed Sheeran’s music has inspired well over a decade’s worth of eye rolls and turned-up noses – not necessarily because it’s bad, in the eyes of critics, but because it’s boring.

That’s not an oversimplification. In 2011, The Guardian’s Peter Robinson literally made the English singer-songwriter the face of “The New Boring,” calling his debut album + “a 12-bore s–tgun” and likening him to “a combination of every friend-of-a-friend’s band whose pub gig you have ever witnessed.” Six years later, Pitchfork’s Laura Snapes described Sheeran as “trite,” “bland” and “unimaginative,” all within the sub-headline of a review about his third album ÷ (it scored a 2.8). For the duration of his career, the musician has been especially critiqued for his approach to genre, cherry-picking features of hip-hop, R&B and rock and distilling them into compressed, radio-friendly pop earworms which inevitably become lodged for years at a time on the charts and on grocery store speakers — writer Rachel Aroesti recently described the end result as a “sludgy, vague, inoffensive post-genre sound that has served to homogenise music in general.”

It’s understandable why people might be so tempted to explain away Sheeran’s success. Homely, scruffy and pointedly underdressed, he soared into the general public’s consciousness as the total antithesis to the polished male pop stars who were big before him — Justins Timberlake and Bieber, One Direction, Bruno Mars – prompting confusion as to how exactly he was able to infiltrate their sleek ranks. But as the essays have piled up over the last 15 years dismissing his scrappy image and mass-appeal music as calculated ploys to maximize profit by appearing as relatable to consumers as possible, one salient quality of Sheeran’s superstardom seems to have fallen out of focus. His seamlessly packaging together the shiniest parts of different genres and presenting them in a way that’s almost universally palatable is a skill in and of itself, and one with which Sheeran is singularly gifted.

It takes an intriguing musical vocabulary, for instance, to infuse a romantic folk ballad such as “Lego House,” one of Sheeran’s earliest hits, with mile-a-minute rap bars — “And it’s dark in a cold December/ But I’ve got you to keep me warm…” in the pre-chorus, without interrupting its cozy pacing. The same can be said of his 2014 smash “Sing,” which somehow has all the body and elasticity of a FutureSex/LoveSounds banger – producer Pharell Williams once told Billboard the Timberlake album was a key inspiration — while staying simultaneously grounded in acoustic instruments and Sheeran’s rapid-fire rhyming. Other hits like 2014’s R&B-rap-pop-dance number “Don’t” and 2017’s tropical 12-week Billboard Hot 100-topper “Shape of You” show off his proclivity for complementing catchy sung melodic hooks with percussive rap-based verses, which he can confidently weave in and out of without ever disrupting the overall feel of a song.

Though he’s never been the most prosaic writer, the words he does choose instead serve to fit snugly in rhyme pockets or push the momentum of a section forward. While certainly cheesy and not particularly clever, the lyrical and melodic simplicity of “I’m in love with the shape of you/ We push and pull like a magnet do/ Every day discovering something brand new” enables it to wedge instantly into listeners’ memories. On the verses, he creates pleasing, percussive toplines that aren’t weighed down by needless syllables, but still manage to propel the narrative forward by quickly summarizing storylines (“One week in, we let the story begin/ We’re goin’ out on our first date”) or tapping into multiple layers of meaning (“We talk for hours and hours about the sweet and the sour…”)

There have been some clunkers in his catalog, for sure: references to Shrek and a—hole bleaching have provided certain songs with needless blemishes, yes. But through all his genre-hopping and unorthodox wordplay, at the very least he can say he’s forged a style that’s entirely his own. His mass appeal may make him “generic” by definition, but his sound is his: Even the successors to his guy-with-a-guitar pop-rock mantle – Shawn Mendes, Lewis Capaldi, Noah Kahan — haven’t once gone near the playful experimentation Sheeran cut his teeth on, instead favoring safer, more traditional songwriting structures.

It’s also notable that Sheeran has never been dishonest about where his scattered musical influences came from, nor has he ever lazily copied anyone else. He’s always stated his love for figures like Damien Rice, Eminem and Eric Clapton, and he worked exclusively with grime artists on the self-released 2011 EP No. 5 Collaborations Project. And at a time where any male artist with his tastes would’ve earned far more cool points by positioning himself as an aloof rock star in the vein of Oasis or Arctic Monkeys, he instead fully, authentically embraced the world of pop and its leaders, teaming up with Taylor Swift on “Everything Has Changed” in 2013 and penning hits for Biebs and 1D (2012’s “Little Things” and 2015’s “Love Yourself,” respectively.)

All of this to say, maybe Sheeran’s songs aren’t just soulless composites of popular genres designed to be as widely played as possible, but the natural blended output of a guy with a genuine love and appreciation for all the styles he employs. He also happens to be very strategic when assembling those puzzle pieces in a song, preternaturally sensitive to which elements are most likely to make for a successful hit – a personal goal he’s long been transparent about chasing. (“I have a data sheet emailed to me every week,” he told GQ with a wink in 2017. “My benchmark for the second album was Coldplay. This album it’s Springsteen.”)

The spectrum of his sound runs parallel to how much he does or doesn’t tailor songs for commercial success. On one end there’s the smoke-blowing songs like 2011’s “You Need Me, I Don’t Need You” and 2017’s “New Man” where he fully indulges his love for loose, slightly silly rapping. Though they might become fan classics, they’re the least programmed to become global hits — he’s just having some fun. On the other end are his sweeping romantic ballads like “Thinking Out Loud,” “Photograph” and “Perfect,” which are maniacally constructed for decades of play at weddings and high school dances. But of these, ask yourself: if not Sheeran, who else is up to the task of pumping out this generation’s deck of timeless sappy slow-dance songs?

In the middle is everything else, the so-called homogenized, post-genre songs that have a little something for everybody. There are several different outcomes songwriters pursue when writing music, and consequently, there are just as many measures of that music’s quality. None are necessarily right or wrong. Swift’s goal is to tell personal stories through her songs. Pitbull wants people to dance. Adele aims to pack an emotional punch. And each of these objectives requires a great deal of craftsmanship when putting pen to paper. Even if Sheeran’s desire has been to write songs surgically stitched together for easy listening, does he really forfeit any recognition for being one of his generation’s most innovative songwriters just because his music is created with algorithmic precision?

When one of his songs ultimately gets stuck in your head for weeks, you might curse his formula as being that of an evil genius. But the key word here is still “genius.”